Soul at the Shore and at The Strip

After the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was signed into law, beach towns across the South began to change dramatically. Before the landmark legislation, Black families flocked to destinations that welcomed them—places where they could dine, find lodging, and enjoy the sand and sea without restriction. Where Black families traveled to shore, so did the Soul music artists. Black-owned hotels and businesses flourished in spots along The Grand Strand, especially in communities like Atlantic Beach and North Myrtle Beach in South Carolina. Known as "The Black Pearl," Atlantic Beach became a lively hub where inland farmers, local workers, and church groups gathered every weekend from April through October, creating a vibrant and memorable summer tradition.

Just a few artists who performed at Carr’s Beach 1960-1969. Illustration by J.D. Humphreys

• SEGREGATED SAND TO SOULFUL SHORES •

Before legislation transformed public spaces, white property owners along Southern beaches often enforced segregation by roping off areas from the dunes to the surf, posting signs to keep Black visitors off their sand. Ray Charles had a memorable encounter with this practice during a trip to Myrtle Beach. Enjoying a carefree swim, he paddled further out, immersed in the joy of the ocean. “I was having a ball, splashing in the ocean like a baby in a bath,” he wrote in his autobiography. “Suddenly, I heard one of the cats screaming, ‘Hey, Ray, come back, man. Come back!’ I thought I had I had simply gone out too far and that the cats were worried about me drowning. But that wasn’t it.” Once back on shore, they told him that he had swam over to the white side. “White side! Shit. Who ever knew of such a thing? I couldn’t figure out how the ocean could have a white and Black side.”

Black entertainers who performed for all-white audiences along segregated Ocean Drive were not permitted to stay after their shows. Once the applause faded, they would travel a few miles to Atlantic Beach, where they could find accommodations and a welcoming community. Venues like the Cotton Club, Black Magic Club, and the Hawk’s Nest became legendary late-night spots, hosting iconic artists like Chubby Checker, James Brown, Otis Redding, Martha & the Vandellas, Tina Turner, Marvin Gaye, the Dixie Cups, the Drifters, Wilson Pickett, and Patti LaBelle and the Bluebelles. These clubs offered not only a place to stay but also a stage to perform freely, creating an unforgettable musical scene that thrived well into the night.

“I couldn’t figure out how the ocean could have a white and Black side.”

- Ray Charles

• THE BEACH MUSIC PHENOMENON •

In the 1960s, while major inland venues boasted headlining acts such as James Brown and top Motown artists, the coastal clubs and smaller venues of North and South Carolina played host to rising and regional musicians. This environment gave rise to "beach music," a vibrant subgenre rooted in rhythm and blues, soul, and rock-and-roll, that came to embody the lively, dance-driven culture of the East Coast beach scene. These venues, with limited budgets, embraced up-and-coming acts and regional bands who helped shape the sound and spirit of beach music.

Rudy Lewis of the Drifters. Illustration by J.D. Humphreys

Groups like Chairmen of the Board, The Dominoes, The Drifters, The Platters, and solo artists such as Brenton Wood, Arthur Alexander, Maxine Brown, Clifford Curry, and Ernie K-Doe became key figures within the beach music scene. Their music, characterized by soulful melodies, catchy hooks, and a danceable beat, created a unique cultural identity that flourished at beach clubs and pavilions. White artists also contributed to the evolution of beach music, adopting a sound distinct from the more elaborate productions of major touring acts with horn sections or orchestras. Their stripped-down, simpler arrangements made the music accessible and appealing in intimate venues, allowing these artists to carve out lasting reputations.

Here are a few “beach music” classics:

Maurice Williams and the Zodiacs – “Stay” (1960)

Maurice Williams, a native of South Carolina, began making music in the 1950s, striving to gain popularity with his group. Renaming themselves The Zodiacs after a car model, they achieved a major breakthrough with "Stay" in 1960. A buoyant, rhythm-driven track that captures the fleeting desire for one more dance before curfew, "Stay" became a #1 hit and remains notable as the shortest song to top the Billboard charts at just 1 minute and 36 seconds. Its hand-clapping tempo and catchy plea of "Stay just a little bit longer" make it a quintessential beach music classic, perfect for dancing and singalongs.

The Drifters – “Under the Boardwalk” (1964)

“Under the Boardwalk” by The Drifters is one of the most iconic beach music tracks, conjuring nostalgia for summer flings by the sea. Originally fronted by Clyde McPhatter, The Drifters' sound evolved over the years, and with Rudy Lewis's unexpected passing, Johnny Moore stepped in to record this hit. The track’s mellow guitar riff, gentle rhythm, and calypso-tinged percussion set a breezy, romantic tone, while Moore’s emotive vocals and the group's harmonies evoke longing and escape. Rising to #4 on the charts, “Under the Boardwalk” captures the essence of seaside romance and remains a timeless beach music anthem.

The Tams – “Be Young, Be Foolish, Be Happy” (1968)

The Tams' “Be Young, Be Foolish, Be Happy” captures the carefree, optimistic spirit central to beach music culture. With its rhythmic bassline, bright horns, and catchy drumbeat, the track immediately invites listeners to dance and enjoy the moment. Lead singer Joseph Pope delivers the song’s message with smooth warmth, supported by jubilant backing harmonies. A chart success, it became a million-seller and a staple for beach music enthusiasts, embodying the genre’s mix of soul, pop, and lighthearted danceability.

The Jewels – “Opportunity” (1964)

“Opportunity” by The Jewels showcases the 1960s girl-group soul sound through its energetic beat and commanding vocals led by Grace Ruffin. Released in 1964, the track features driving rhythms, vibrant horns, and strong backing harmonies that emphasize themes of ambition and seizing chances. Although overshadowed by bigger names in the girl-group scene, The Jewels left a lasting impact within the beach music community, where their call-and-response vocals and assertive delivery made “Opportunity” a beloved track. The song’s message of resilience resonated, particularly amid the social challenges faced by African Americans at the time, giving it lasting cultural significance.

• CARR’S BEACH •

Just a stone’s throw from Annapolis, Maryland, lies a serene stretch of Chesapeake Bay shoreline that once flourished as Carr’s Beach. Today, the name evokes only memories of what was a vibrant oasis for Black families during the early 1960s, a time when this picturesque retreat transformed into a lively haven amid the restrictions that barred them from more popular white beaches. Nestled along Annapolis Neck, Carr’s Beach was not just a beautiful spot to relax; it pulsated with the electrifying energy of entertainment, amplified by WANN radio’s Hoppy Adams.

An oasis of Soul music and merriment, Carr’s Beach hosted an array of legendary artists, including the Temptations, the Marvelettes, James Brown, Ike & Tina Turner, the Shirelles, and Little Richard, drawing crowds eager to experience the thrill of live performances. This vibrant venue had been a cultural cornerstone since the 1940s, providing a vital platform for artists to connect with their audiences. For many Soul musicians, Carr’s Beach was often the final stop after shows in Washington, D.C., and Baltimore before heading home or continuing south on the Chitlin’ Circuit.

LISTEN TO CARR’S BEACH RADIO COMMERCIAL FROM 1966

One unforgettable event at Carr’s Beach on July 21, 1956, drew an astounding crowd of approximately 70,000 people eager to see Chuck Berry take the stage. However, only about 8,000 fortunate attendees could actually fit within the venue's limits. The excitement for live music at Carr’s Beach didn’t stop there; a 1962 performance by the legendary James Brown attracted an enthusiastic audience of 11,000 fans, further solidifying the beach's reputation as a premier destination for iconic Soul performances.

As the vibrant sounds of Soul music reverberated through Carr’s Beach, white kids from the surrounding area started to catch wind that their favorite artists were performing nearby. Fueled by curiosity and a longing to soak in the electric atmosphere, many of them slipped in to catch the shows. By the early 1960s, it was increasingly common to see these young fans mingling in the crowd, where they were welcomed and accepted, contributing to an emerging sense of racial unity through the power of music. Gathering at Carr’s Beach was not just a celebration of the performers' artistry; it also cultivated connections that broke through the barriers of segregation.

“It was at the beach that racial segregation began to break down. White kids could listen to R&B behind their folks’ backs.”

- Chairman Johnson of Chairman of the Board

“It was at the beach that racial segregation began to break down,” said Chairman Johnson of the group Chairman of the Board. “White kids could listen to R&B behind their folks’ backs.”

With the end of legal segregation, Black businesses and hotels began to lose the loyalty they once held. Black tourists now had expanded options for comfort and convenience in newly integrated establishments, leading many to explore areas that had previously been off-limits. As a result, The Black Pearl, once a thriving hub of Black culture and community, would never be quite the same.

• CHANGE COMES TO LAS VEGAS •

In the 1960s, Las Vegas blossomed into a glittering resort town, its neon lights and vibrant entertainment scene attracting Black performers who brought brilliance to The Strip. Yet, beneath the glitz and standing ovations lay a harsh reality: these stars were required to enter and exit venues through back doors and kitchens, and once their performances ended, they were prohibited from staying in the very hotels where they captivated audiences. Instead, they had to travel miles to boarding houses in West Las Vegas—a stark reminder of the racial inequalities overshadowing their achievements. By the 1950s, Las Vegas had earned the grim nickname “Mississippi of the West.”

“We came to the shows dressed in costume because there were no dressing rooms for Blacks,” said Claude Trenier, leader of the Treniers. “Between acts, we were told to go out and wait by the pool. Harry Belafonte once went swimming with his kids at the hotel where he worked, and the next day they shut down the pool, drained it and cleaned it.”

“We came to the shows dressed in costume because there were no dressing rooms for Blacks.”

- Claude Trenier of the Treniers

In the 1950s, during Ed Sullivan's visit to Las Vegas, a production meeting at a Strip resort unfolded with a mix of music industry heavyweights, including singer Della Reese. When Reese requested a simple cup of coffee while seated among the white executives, the waitress flatly refused to serve her. Witnessing this blatant act of discrimination, Joe Delaney, a white executive from Decca Records, quietly stepped in. He ordered the coffee himself and slid the cup over to Reese. The consequences came swiftly—a phone call from a hotel official warning Delaney to "not cause trouble." Reflecting on the threat, Delaney later remarked, “I knew exactly what he meant.”

Delaney explains, “You have to remember the industry was casino—not hotel-driven. A lot of the big business at the time was from Texas and Oklahoma oil men and cattlemen who did not want to see, as they put it, ‘nigras’ in the hotels.”

Sammy Davis Jr. Illustration by J.D. Humphreys

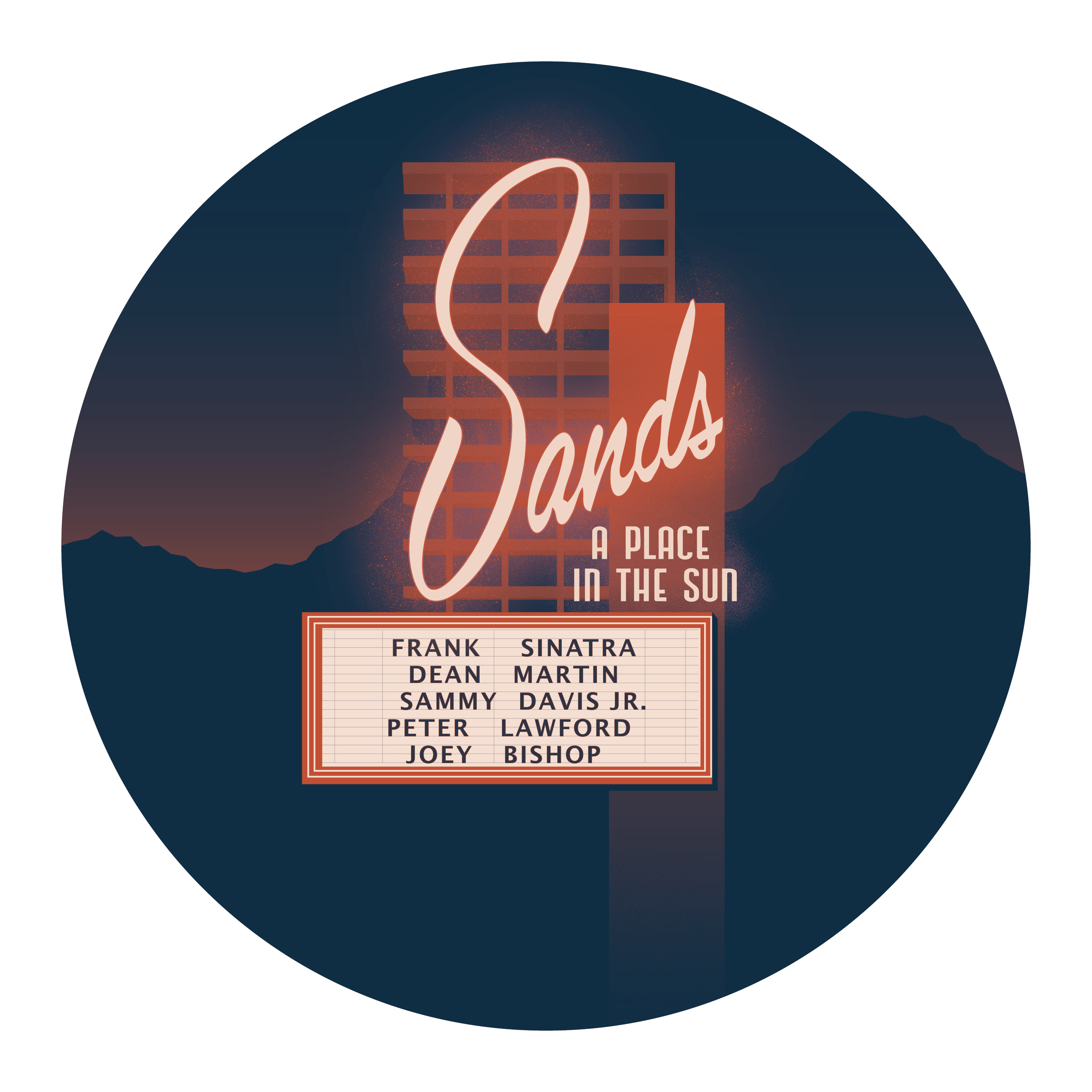

Sammy Davis Jr. was a powerhouse in Las Vegas, renowned for his film roles, Broadway performances, and unmatched charisma. In the early 1960s, he took the stage alongside Frank Sinatra, Dean Martin, Peter Lawford, and Joey Bishop at the legendary “Summit at the Sands” shows. Dubbed the “Rat Pack,” this group redefined cool, delivering electrifying, unscripted performances that became the hottest ticket in town.

But behind the glamour, Davis faced a grim reality. Initially, he was denied a room at the Sands Hotel due to his race. Enter Sinatra, whose loyalty transcended beyond the stage. Sinatra threatened to cancel their shows unless Davis was allowed to stay. Management caved, setting a powerful precedent and breaking barriers for Black entertainers. This bold move cracked the discriminatory practices that had forced many Black stars to seek shelter in West Las Vegas boarding houses, miles from the bright lights of The Strip.

Las Vegas reached a pivotal crossroads in 1960 when the NAACP, led by Dr. James McMillan, issued a powerful ultimatum: a mass protest and economic boycott targeting the city’s casinos if segregation continued. Alarmed by the potential disruption to their lucrative businesses, city officials, civil rights leaders, and key figures from the hotel and casino industry convened in a secret meeting on March 26, 1960. The result was a groundbreaking agreement to desegregate hotels and casinos along The Strip and downtown Las Vegas.

This landmark move cracked open the door to integration, reshaping the city’s future. However, the struggle was far from over. The shadows of racism and discrimination persisted, even as new foundations for equality were being laid.

WATCH “THE RAT PACK” PERFORM AT THE SANDS IN 1960

For jazz singer Nancy Wilson, Las Vegas presented a strikingly different reality compared to the Black performers who came before her. “The Lena Hornes and the Billie Holidays and the Nat Coles, they walked in the back doors in Las Vegas,” she said. “I walked in the front door, headlining.”

When Las Vegas' casinos and hotels were finally desegregated, the once-thriving Jackson Avenue, a hub for Black clientele, began to fade. Freed to patronize venues that had long been barred to them, customers gradually drifted elsewhere, leaving behind cherished neighborhood establishments.

Jim Crow laws cast a dark shadow, deeply unjust and demoralizing, but they could not silence the power of art. Music refused to be caged; it crossed boundaries and erased barriers, slipping past ropes that once divided audiences. As melodies swept through rooms, Black and white feet found rhythm together, and on the dance floor, unity briefly triumphed over separation.

“We came back that next year and the rope was gone,” said Otis Williams of the Temptations. “And we were singing, and luckily we were sweating so, that had it not been for the sweat, you would have seen our tears, because we were crying just to see what music could do to bring people together.”

“…we were crying just to see what music could do to bring people together.”

- Otis Williams of the Temptations