White Supremacy and the Suppression of Black Excellence

When “The Nat King Cole Show” aired on NBC in 1956, it was significant milestone and showcased his talent as a Black musician and entertainer. Its popularity did not shield it from racial onslaught so prevalent during this changing time. A glaring example was that the network required Cole to wear makeup that made him appear lighter-skinned to make him more palatable to white audiences and advertisers, also known as “whitewashing.”

Nat King Cole. Illustration by J.D. Humphreys

Months earlier, Cole performed live to an all-white audience of 3,500 in Birmingham, Alabama where three men, associated with the North Alabama Citizens Council, charged the stage, and knocked Cole to the ground. According to newspaper accounts, the horrified audience watched as the men were quickly apprehended. Ted Heath and his band, who toured with Cole, was so livid that he considered cancelling the tour, though Cole talked him out of it.

Cole, who experienced oppression throughout life, faced additional challenges and discrimination as a Black celebrity in the public eye. When the Cole family moved into a Tudor mansion in the all-white neighborhood of Hancock Park in Los Angeles in 1948. He faced significant hostility from his new neighbors, who staged protests and circulated petitions in an effort to force him to move out. If that was not enough, racists burned epithets on the family’s lown and poisoned the family’s dog. A year later, things worsened when a bullet went through one of the windows. Cole had paid $65,000 for the mansion just to face an $85,000 covenant battle. By then, the neighborhood made it clear they did not want any “undesirables” living there. Cole’s dignified response was a promise to raise the alarm if he discovered any “undesirables” there, reassuring them that as a responsible and respectful neighbor, he shared their concerns and wanted to maintain a safe and secure neighborhood.

“They all had his [Cole’s] records in their house, but they signed the petition to get him out.”

- Musician George Benson, “Nat King Cole: Afraid of the Dark”

“All the people who were protesting that he moved to their neighborhood were protesting for another reason—they were afraid of their property values,” remarked musician George Benson in the documentary Nat King Cole: Afraid of the Dark. “They all had his records in their house, but they signed the petition to get him out.”

The incident years later at the Birmingham Municipal Auditorium was headed by Asa “Forrest” Carter and the intention had been to kidnap Cole and to discourage other Black performers from visiting the city. A white supremacist, Carter claimed Rock & Roll music “is the basic heavy beat music of negroes. It appeals to the base in man, brings out animalism and vulgarity” and it is with no surprise he would later pen Governor George Wallace’s “segregation forever” speech. He believed rock music was part of an “NAACP plot to mongrelize America” and impose “Negro culture” on the South.

Cole was midway through his third song, “Little Girl,” when the attack happened on stage. The audience confused the move as an attack on the drunk man who was taunting Cole near the front row, ‘Negro, go home.’ As plainclothes policeman rushed in to protect Cole, uniformed officers clashed with them thinking they were with the perpetrators.

“I just came here to entertain you,” he told the crowd when he made his way back to the stage minutes later and greeted with applause. “That was what I thought you wanted. I was born in Alabama. Those folks hurt my back. I cannot continue, because I need to see a doctor.” He left the stage, got examined by a doctor, and returned to perform at a scheduled Black-only show later that evening. Officers would later search one of the attacker’s cars to find brass knuckles, a blackjack, and rifles. The motive was clear. All men involved in the attack were tried and convicted.

The incident gave him pause and self-reflection. Cole knew he alone could not stop the systemic bigotry in places like Alabama and remarked, “I can’t understand it… I have not taken part in any protests. Nor have I joined an organization fighting segregation. Why should they attack me?”

Why he even played in the South, Cole told Jet Magazine, “Those people, segregated or not, are still record fans. They can’t overpower the law of the South, and I can’t come in on a one-night stand and overpower the law. The whites come to applaud a Negro performer like the colored do. When you’ve got the respect of white and colored, you can ease a lot of things. I can’t settle the issue—if I was that good I should be President of the United States—but I can help to ease the tension by gaining the respect of both races all over the country.”

“Even if they sit one separate sides of the room, maybe at intermission a white fellow will ask a Negro for a match or something, and maybe one will ask the other how he likes the show. That way, you have started them to communicating, and that’s the answer to the whole problem.”

- Nat King Cole

Cole had performed in Southern auditoriums that were either non-segregated and segregated down the middle. The contract for his Birmingham performances called for two separate shows, one for an all-white audience and another for an all-Black audience. “The important thing is for Negroes and whites to communicate,” he added. “Even if they sit one separate sides of the room, maybe at intermission a white fellow will ask a Negro for a match or something, and maybe one will ask the other how he likes the show. That way, you have started them to communicating, and that’s the answer to the whole problem.”

A month after the Birmingham incident, Cole recorded “We are Americans Too,” a radical departure from his usual love songs and promoted brotherhood and unity among Americans. However, it was so sincere that Capitol Records did not release the song because they feared it might be too controversial and could jeopardize Cole’s deal with NBC.

Cole now appeared to be passive, or even worse by complying with the demands of white society as a sellout. Therefore, Cole faced harsh criticism from leaders in the Black community. Thurgood Marshall, chief legal counsel of the NAACP, labeled Cole an “Uncle Tom” and asked why he did not perform with a banjo. The Black press, such as the Chicago Defender, claimed Cole’s performances to all-white audiences were an insult to his race and that playing “Uncle Nat’s” music "would be supporting his 'traitor' ideas and narrow way of thinking."

Deeply disturbed by the criticism, Cole further reflected on his role as a public figure and the impact he had on white and Black audiences. With the realization that he could not miss the opportunity to advocate for greater social justice and equality, he denounced any form of segregation, and boycotted segregated venues, and became a lifetime member of the Detroit NAACP. Cole immersed himself in the planning the March on Washington in 1963 and kept the commitment as one of the more visible artists to support and participate in the Movement up until his death in 1965.

Chuck Berry. Illustration by J.D. Humphreys

When Chuck Berry rose to stardom, he was also targeted by rock haters. In August 1959, a 20-year-old white woman and her boyfriend approached Berry for an autograph after his performance in Meridian, Mississippi. Berry was promptly arrested on suspicion of propositioning a white girl, a crime under the state’s anti-miscegenation laws at the time. He was released the following day after posting bail. That same year, Berry was arrested under the Mann Act for “transporting a minor across a state line for immoral purposes.” Berry had transported a 14-year-old girl across state lines to work at his nightclub in St. Louis, Missouri. The Mann Act was passed in 1910 and used to target Black men, particularly those were suspected of or involved with white women. Berry was convicted and sentenced to prison, though the case was later appeal and ultimately dismissed. The act’s main purpose was a create a crime out of interracial, yet consensual, sexual activity and to substantiate the claim that America was somehow being mongrelized and that Black people could be put in their place, especially Black celebrities such as Berry.

LISTEN TO “TUTTI FRUTTI” BY LITTLE RICHARD

Hostilities towards rock music had a profound effect on some artists, who were sometimes labeled as immoral, obscene, or subversive by their detractors, often religious leaders who fed the falsehoods from the pulpit. This type of criticism could be very damaging to the careers and reputations of artists and some artists who were devoutly religious themselves faced a difficult, if not impossible, balancing act to reconcile their faith with the perceived immorality of their chosen profession. Richard Wayne Penniman, known as Little Richard, was known to be eccentric and flamboyant in his gender-bending performances, frequently toggled between masculine and feminine behavior with exaggerated mannerisms and poses that challenged traditional gender norms. He created a number of hits including “Tutti Frutti” in 1955 which some suggest was an ode to anal sex, though Penniman denied it in interviews: “Tutti Frutti, good booty / If it don’t fit, don’t force it / You can grease it / make it easy.” The lyrics to “Tutti Frutti” were deemed too vulgar by Specialty Records execs and white radio stations refused to play the song even after the song lyrics were sanitized to “Tutti Frutti, all rooty!” Yet in 1956, when white singer Pat Boone covered the song, essentially “whitewashing” it, record execs had an about-face.

Richard Wayne Penniman, known as “Little Richard.” Illustration by J.D. Humphreys

“They didn’t want me to be in the white guy’s way… I felt I was pushed into a rhythm and blues corner to keep out of rockers’ way, because that’s where the money is,” Penniman said. “When ‘Tutti Frutti’ came out, they needed a rock star to block me out of white homes because I was a hero to white kids. The white kids would have Pat Boone upon the dresser and me in the drawer ‘cause they liked my version better, but the families didn’t want me because of the image I was projecting.”

Penniman was very unhappy that Boone had swooped in and whitened “Tutti Frutti.” As a result, he would record tunes even faster in hopes that Boone would not be able to keep up.

“I mean, I don’t know which was worse, Pat Boone stealing Little Richard’s song ‘Tutti Frutti’ and making it a hit in white America,” said jazz singer Nancy Wilson. “You’re playing us and killing us different ways, same way.”

Penniman’s creativity earned him several hits including “Long Tall Sally” in 1956 and “Good Golly, Miss Molly” in 1958 furthering the evolution and definition of early Rock & Roll. He also brought mixed audiences together at performances, even venues that were segregated.

“I knew what Little Richard was singing was very different from what Pat Boone was singing even when Pat Boone sang the same song.”

- Paul Breines, Freedom Rider

“I would go to parties and typically the music would be Elvis Presley or Pat Boone,” recalled Paul Breines, one of the Freedom Riders in the documentary Let Freedom Sing. “But for me I knew what Little Richard was singing was very different from what Pat Boone was singing even when Pat Boone sang the same song. What had happened it had to do with was a kind of a creativity which was not coming from the immediate world that I was in – white people. And I knew very few people in my class in high school would be interested in that music because it was too, so to speak, ‘colored.’ It was too tainted, it was too outside and some way that was what I liked about it.”

Penniman’s pancake makeup, curled hair, crazy costumes, and painted eyebrows broke societal norms in the 1950s. Later, Penniman opened about his cross categorical queerness, identifying as both bisexual and gay at different points in his life and even coined the term “omnisexual” to describe his complex sexual identity. Penniman had a past life as Princess LaVonne, a drag queen who traveled in Black entertainment circuit shows in the late forties. As a youth, he was called a “faggot” though it did not deter him from powdering his face in the school bathroom, perusing Macon’s gay underworld, and orchestrating group sex so that he could watch. When he introduced himself as “Little Richard, King of the Blues… and the Queen, too!” at the Club Matinee in Houston in 1953, he did so with all seriousness and candor. Given his androgynous appearance and flamboyant style, rumors were often used against him and he faced obstacles that his white counterparts did not have to deal with. However, that did not stop young women from offering Penniman nude photos and their phone numbers. Identifying as anything other than heterosexual in the 1950s was considered highly taboo and very few artists were out. Billy Wright, a musician who was also part of the Black entertainment circuit, was one of the few openly queer artists of the time.

Too queer and too Black, Penniman reportedly earned only half a penny per record sold, compared to the three to five cents paid to white stars. Additionally, Penniman did not collect royalties when his tunes were used in movies or covered by white singers, which would have furthered his earning potential. A common practice in the music industry at the time, it disproportionately impacted Black artists who were often excluded from the financial benefits of their own work.

Little Richard confuses Sputnik for a sign from God to repent. Illustration by J.D. Humphreys

In October 1957, Penniman saw a sign from God in the sky while performing in Australia. A stadium full of rowdy teenagers scrambling to grab his discarded clothing did not distract from the big ball of fire that zipped across the sky over Sydney. Penniman, in panicked awakening, interpreted the ball as the message to leave show business, abandon the devil’s music, and pursue a more religious path.

“It looked as though the big ball of fire came directly over the stadium about two or three hundred feet above our heads,” he later recalled to his biographer, Charles White. “It shook my mind… I got up from the piano and said, ‘This is it. I am through. I am leaving show business to go back to God.’”

The fiery ball that horrified Penniman was Sputnik, the Russian satellite traveling 18,000 miles per hour in the night sky. Sputnik was a groundbreaking achievement in space exploration and its launch was highly anticipated and monitored by countries around the world. Days later he spoke to presenter Jack Davey about it while still in Australia.

“We hear so many tales about you,” Davey began as the audience broke out in laughter. “Just the nicest things.” Penniman joins in with the laughter, knowing that his eccentric behavior and flamboyance was top of mind. Davey then mentions the news that he is leaving music.

“Yes, I’m anxious to get back to America but I’m coming out of show business,” Penniman responds. “I’m going to be an evangelist. The reason—I would like to say this, I’m glad you asked me—but the reason I want to come out of show business, you see, is all these different kinds of lights going up in the sky.” The audience erupted in laughter again, finding his statements ridiculous.

“The reason I want to come out of show business, you see, is all these different kinds of lights going up in the sky.”

- Little Richard in an interview with Jack Davey

“You mean the satellites?” Davey cuts in.

“That’s right, that’s it. And that’s a sign that the Lord is coming soon and I want to dedicate my life to God.”

“I see, Little Richard,” Davey said. “That’s a very good thought. It has worried you, this satellite?”

“Oh no, it don’t worry me so much but I know that if I don’t get it right, I know that the plans that the Lord is going to put on the world, they going to worry me so I might as well worry one way or the other.” Penniman, in front of an audience, had misunderstood Davey’s questions and struggled to explain his thinking.

“So, I’m going back and I want to study so I can help the other people doing wrong so they can be saved too,” he added. Penniman insisted that while music can be good, he could not “serve the Lord while I’m doing this because he said you either love one or hate the other, either hold one or turn loose the others, so I got to get completely from this to dedicate my life directly to God.”

Penniman abandoned secular music altogether and his abrupt decision had significant consequences. He had to cancel numerous bookings, which resulted lawsuits and lost revenue, even reportedly owing hundreds of thousands of dollars to his management and booking agents. After a brief unsuccessful stint in Bible college and marriage to a woman whom he later divorced, Penniman returned to secular music with an attempt to pick up where he left off. The music industry changed so much during his absence and he was not initially successful. He struggled with his own identity and sexuality and would later speak about his drug addiction and depression during this time.

James Brown was the target of conspiracy theories as he rose to fame, including engaging in shady business deals or by suppressing the careers of other musicians. A wild rumor circulated he had been beaten up by his hairdresser, Frank McRae. A fist fight ensued and Brown’s physical prowess as an ex-boxer was no match. Brown had been upset that McRae did not stand his ground when he was pulled over by a police officer who addressed him as a “nigger.”

Like Penniman, Brown’s sexuality was questioned when he adopted makeup techniques popular by Black women at the time. A friend from his boyhood described Brown as “gone sissy.” By late 1965 in the South, rumors traveled that Brown sought corrective surgery to change to a woman.

Like Penniman, Brown’s sexuality was questioned when he adopted makeup techniques popular by Black women at the time. A friend from his boyhood described Brown as “gone sissy.” By late 1965 in the South, rumors traveled that Brown sought corrective surgery to change to a woman.

“‘James Brown is going to change himself to a woman’ was the rumor that was circulating as late as last week among the teenagers, and now it has spread among the adults,” the Houston Forward Times reported.

Brown would later create a rumor of his own, seeing it as a publicity stunt, by announcing that he was marrying Bobby Byrd of the Famous Flames, who he had met in juvenile prison, but only after Byrd had completed his sex change to a woman.

Ray Charles was one of the first artists to reject Jim Crow laws in the fifties. Even into March 1962, he was sued and fined for refusing to play a scheduled date in Augusta, Georgia, after he learned the Bell Auditorium was segregated with the Black audience members being relegated to the balcony. The promoter sued for breach of contract and Charles was fined $757.50 by the state of Georgia. Two years earlier, Charles, a native Georgian, recorded “Georgia On My Mind” that went to number one on the Billboard Hot 100. Almost two decades later with reconciliatory intent, the state of Georgia adopted it as the state song.

“My version of Georgia became the state song of Georgia,” Charles remarked. “That was a big thing for me, man. It really touched me. Here is a state that used to lynch people like me suddenly declaring my version of a song as its state song. That is touching.”

With mainstream media slowly changing to incorporate Black programming and acts, the 1950s marked a period of significant change and activism. During this time, there were a number of landmark events and courts cases that helped advance the cause of civil rights, including the Brown v. Board of Education decision in 1954, which struck down the “separate but equal” doctrine that had allowed for segregation in public schools. While the South was championing Jim Crow laws, many Northern areas had de facto segregation policies in place that limited opportunities for Black Americans. One of the most significant areas of inequality was in education, where there was a wide gap in resources between white and Black communities. This educational disparity was further compounded by housing discrimination, making it difficult for Black families to move into neighborhoods with better schools and resources. As a result, many Black families were trapped in areas with limited opportunities and little chance for upward mobility.

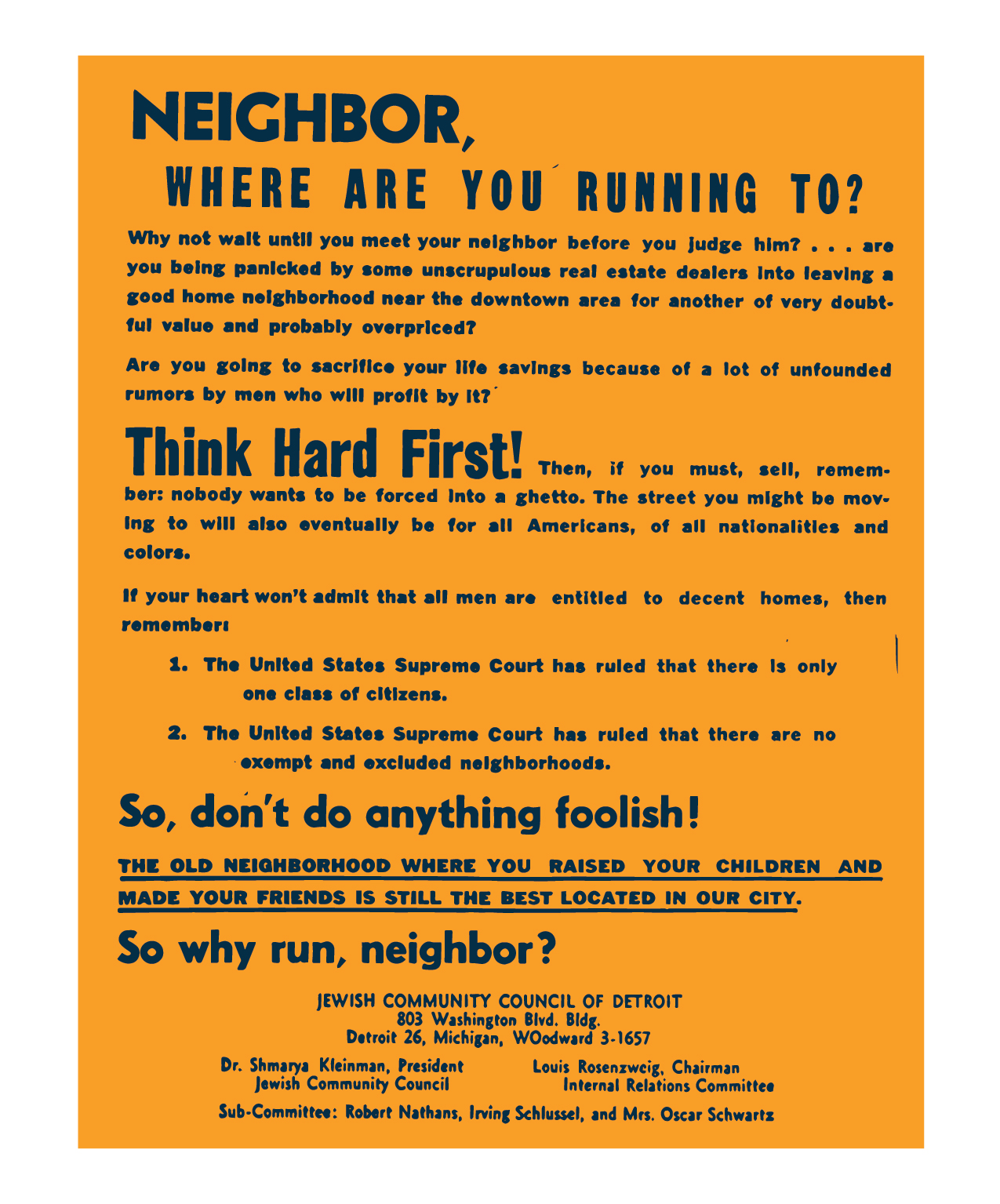

The 1950s and 1960s also marked an era of racial migration, known as “white flight.” Black families experiencing unjust Jim Crow laws of the South and economic challenges, moved their families to urban cities for a new life and work. The term “white flight” is often contentious as many experts point out whites vehemently defended their turf through violence, intimidation, and legal tactics, known as “redlining.” Many white families moved out of urban areas and into suburban neighborhoods and took with them their financial resources and political power, leaving behind a less prosperous and less influential population. This led to increased segregation and inequality and widened the economic and social divide between the urban and suburban communities. In the 1940s, more than ninety percent of Detroit residents were white. Desegregation was a catalyst for demographic change in many American cities. As more Black students were allowed to attend formerly all-white schools, white families often chose to move their children to different schools, private schools, or districts to avoid integration. In 1957, 2,023 white students and 34 Black students were enrolled at Clifton Park Junior High School in Baltimore, Maryland. By 1967, there were only 12 white students and 2,037 Black students.

The 1950s and 1960s also marked an era of racial migration, known as “white flight.” Black families experiencing unjust Jim Crow laws of the South and economic challenges, moved their families to urban cities for a new life and work. The term “white flight” is often contentious as many experts point out whites vehemently defended their turf through violence, intimidation, and legal tactics, known as “redlining.” Many white families moved out of urban areas and into suburban neighborhoods and took with them their financial resources and political power, leaving behind a less prosperous and less influential population. This led to increased segregation and inequality and widened the economic and social divide between the urban and suburban communities. In the 1940s, more than ninety percent of Detroit residents were white. Desegregation was a catalyst for demographic change in many American cities. As more Black students were allowed to attend formerly all-white schools, white families often chose to move their children to different schools, private schools, or districts to avoid integration. In 1957, 2,023 white students and 34 Black students were enrolled at Clifton Park Junior High School in Baltimore, Maryland. By 1967, there were only 12 white students and 2,037 Black students.

With the influx of transplants, cities became areas of change, created tensions that contributed to a wave of riots and civil unrest that swept the country during the 1960s. These riots were often sparked by incidents of police brutality or discrimination, but also fueled by broader social and economic tensions. With schools desegrated, many white and Black youth gained even greater proximity, listened to the same records, exposed to the same cultural trends, to foster a sense of commonality among young people from different backgrounds.